As a collaborative art form, theatre merges words, movement, sound, and light into a single living staged experience. Amidst these sensory layers, one of the most powerful and immediate elements is the visual world in which the story unfolds: what’s commonly referred to as the Set, or Scenic Design.

From the role of the Scenic Designer, their collaboration with the rest of the production team — particularly with the Master Carpenter — and how the physical environment of the stage can be used to create both realism and fantasy, it’s not just about building walls or painting backdrops — it’s about providing the fabric that supports and amplifies the telling of a story.

My name’s Peter Fernandez, and in this article, I’ll be exploring the artistry, psychology, and craftsmanship behind theatrical scenic design, and discussing ways in which scenic design can help elevate a play far beyond the script itself.

Purpose of Scenic Design

At its heart, scenic design exists to serve the story; the work of a scenic designer is not just about decoration or spectacle for its own sake, but about creating a world that supports the director’s vision, complements the performances, and engages the audience’s imagination.

A set doesn’t just establish where and when the play takes place — but also how it takes place. The difference between a minimalist platform and a hyper-detailed period interior tells us instantly how the production expects us to interpret the story.

For example, a bare stage with only a few symbolic elements might emphasise the universality of Shakespeare’s language, while a richly detailed Edwardian sitting room in something like The Importance of Being Earnest, say, situates us firmly in a world of manners, repression, and social codes.

Beyond place and time, scenic design also communicates tone. A tilted floor or skewed doorway can suggest instability or madness; an open, airy space can create freedom or vulnerability. Even the materials used — rough wood versus polished steel, soft drapery versus concrete textures — can evoke emotion. The set becomes a visual metaphor for the internal states of the characters and the themes of the play.

The Emotional Power of Space

Ultimately, space itself is the most powerful tool when it comes to scenic design. Space defines relationships between characters, between the audience and performers, and between reality and imagination. A cramped room can heighten tension; an open void can evoke loneliness. Levels, distance, and perspective guide the audience’s focus and shape their emotional response.

In this sense, scenic design is an architecture of emotion, where every wall, doorway, and platform becomes part of the psychological landscape of the play. As its architect, the scenic designer sculpts space as a composer shapes sound — balancing rhythm, tension, and release.

Role of the Scenic Designer

Whether constructing a realistic apartment, a surreal dreamscape, or a minimalist void, the scenic designer’s art is to make the invisible visible — to render emotion in wood and fabric, and to translate the director’s and playwright’s vision into a shared, living experience.

The Scenic Designer (a.k.a. Set Designer) is both an artist and engineer, dreamer and problem-solver. Using the stage, their primary task is to translate the director’s vision into a physical environment that is both beautiful and functional.

The Process of Scenic Design

Having read a script multiple times, the scenic designer will identify not only the literal locations required by the text but also the emotional journey of the piece. They ask: What is the core atmosphere of this story? What visual metaphors could express its themes? How should the audience feel when they first see the stage?

The Initial production meetings between the director and other members of the artistic team are typically where the directorial concept is discussed.

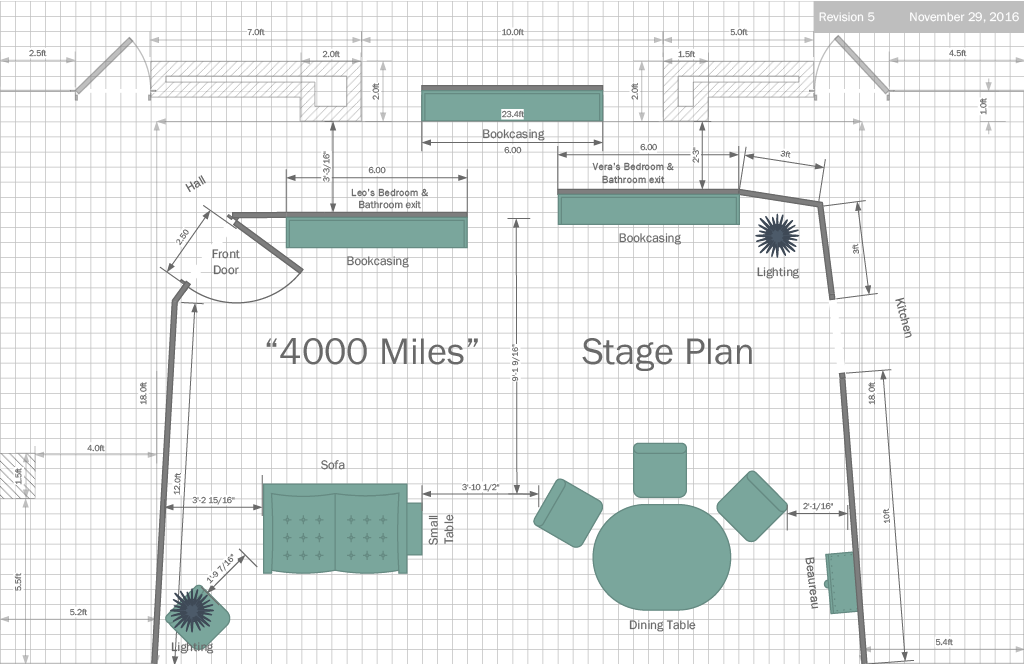

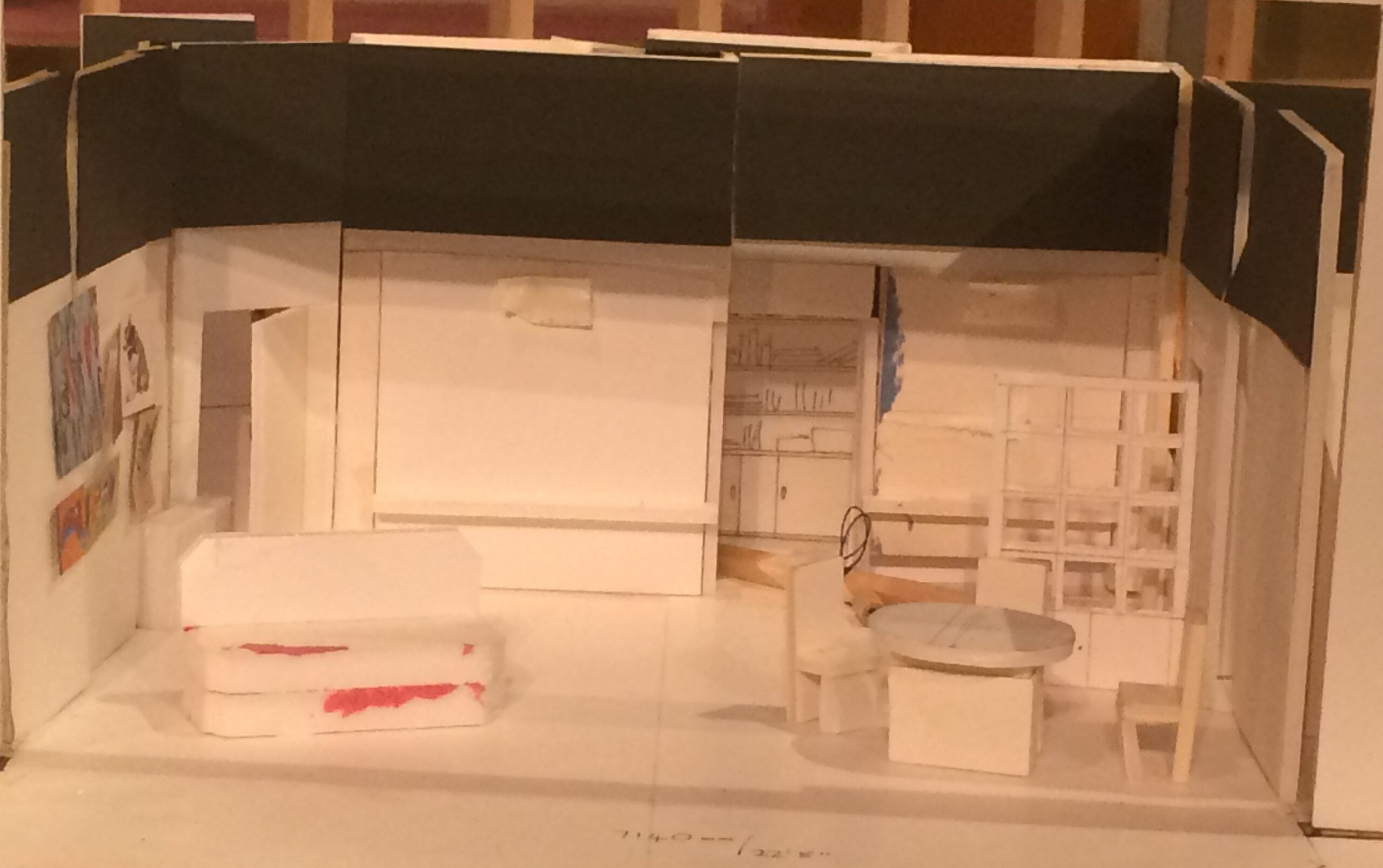

From there, a designer will begin sketching rough visual ideas, floor plans, or digital concept renderings. These early designs evolve into floor plans, elevations, and eventually a 3D model (either physical or digital). The goal is to establish the spatial language of the production: how performers will move, where entrances and exits occur, and how set pieces can change between scenes.

In smaller/community productions, it’s the Scenic Designer may opt to enlist the help of others when producing the floor plans, elevations and/or the model box.

As an example, below are some images from a production of 4000 Miles I was directing, illustrating the Model Box created by Set/Scenic Designer — Annetta Broughton — that translated my two-dimensional stage plan into something easier to visualise. Whilst, as the Director, it was my job to ensure all visual and auditory elements aligned with the directorial concept, I had to remember that (as the Director), my job was to guide rather than dictate — allowing Annetta creative freedom over her part of the design process.

A scenic designer must also consider practical logistics: safety, sight-lines, storage, and the theatre’s specific dimensions. The most brilliant conceptual design is meaningless if it cannot be built safely or within budget. Hence, the art of scenic design lives at the intersection of creativity and pragmatism — a balance of vision and feasibility.

From Research to Development

Every scenic design begins with research. The designer immerses themselves in the world of the play — historically, geographically, culturally, and symbolically. This might involve studying photographs, paintings, films, or architecture relevant to the period or tone.

From their research, the designer develops the visual concept — the plans, models and guiding ideas that shape every design choice. This concept acts as a filter, ensuring that every scenic decision — colour, shape, material — contributes to a unified thematic vision:

- A production of Macbeth that uses cold, metallic textures to suggest brutality & fate.

- A modern production of A Doll’s House that uses transparent walls to symbolise surveillance and vulnerability.

- A musical production of Cabaret that merges realism (i.e. a Berlin nightclub) with expressionism to convey the fractured psychology of pre-war decadence.

Collaborating with the Scenic Designer

Scenic design does not exist in isolation. It must harmonise with every other design element to create a cohesive theatrical language. The best theatrical experiences arise when all departments collaborate as one ensemble of artists, each contributing their discipline to a unified aesthetic and emotional vision.

Working hand in hand with the rest of the creative team, a scenic designer ensures that the audience doesn’t just watch a story — they enter it. The result is not mere scenery, but a complete sensory world: one that captures the heart and imagination, long after the curtain falls.

Scenic Design and Direction

The scenic designer collaborates closely with the director to interpret the story’s emotional and thematic essence; the directorial concept, in other words. Some directors prefer a naturalistic world, whilst others seek abstraction or metaphor. The designer must align with the vision, offering visual solutions that enhance the storytelling.

Scenic Design and Lighting

Light and scenery are inseparable — a lighting designer uses the set as a canvas, emphasising texture, depth, and mood. Strategic placement of scenic elements can give the lighting designer more creative freedom; scenic design must consider how materials respond to light: will a surface reflect or absorb? Will it glow under colour changes? Etc.

Scenic Design and Sound

Sound defines the aural space that complements the visual one. If a set contains hidden speakers, a hollow floor, or moving scenery, these must be coordinated early in the process. Similarly, the construction of scenery that obfuscates sound or that uses materials which could distort sound needs careful planning with the sound designer ahead of time.

Scenic Design and Costumes

Set and costume share a colour palette and stylistic coherence; a character’s costume should neither clash nor vanish against the backdrop. In stylised productions, both designers may use colour and texture symbolically, creating visual hierarchies or emotional contrasts.

Scenic Design and the Master Carpenter

While the designer conceives the world, it is the Master Carpenter (or Master Craftsman) who leads the team that physically brings that world to life. Their relationship is one of the most crucial collaborations in theatre production.

The role of the Master Carpenter — often referred to as the lead set builder — is to lead the team of people responsible for translating the Scenic Designers’ plans into the actual physical on-stage set. Often, this is achieved by assembling pre-fabricated elements, known as “flats”, together with any bespoke construction that might be required for, say, a rostrum, raked stage, or the like.

With smaller/community productions, it’s not uncommon for the Scenic Designer and the Master Carpenter roles to be combined into one.

The Master Carpenter interprets the designer’s technical drawings and converts them into buildable structures. They lead the scenic construction team, select materials, plan the build schedule, and solve the practical challenges of assembling the set within the theatre’s constraints. This role requires both artistic sensitivity and technical mastery: a deep understanding of how wood, metal, foam, and paint can be manipulated to achieve the designer’s vision while ensuring safety and stability.

Communication between the designer and carpenter must be precise. A small misunderstanding in scale or material choice can result in days of extra work or a structural problem that jeopardises the design. Regular meetings, clear drafting, and constant dialogue are essential.

For example, if a designer envisions a “floating” staircase, the carpenter must determine how to build it in a way that truly supports an actor’s weight. Similarly, if the designer calls for a rotating platform, the construction team must design a turntable mechanism that operates smoothly and quietly. In this way, the artistry of the design and the craftsmanship of construction merge into one seamless creation.

This collaboration doesn’t end once the set is built. During get-in and tech rehearsals, adjustments often occur — a wall may need to move, a door may not align with blocking, or an actor may request additional space. The scenic designer and carpenter work together to fine-tune these details, ensuring both artistic integrity and functionality.

From Scenic Design to Reality

The scenic designer typically produces the technical drawings — including ground plans (bird’s-eye view), elevations (front views), and detailed drawings for construction — that the Master Carpenter and team use to build the set.

The materials chosen for construction depend on budget, portability, and safety. Scenic carpenters typically use lumber, plywood, steel, muslin, and foam, while scenic artists add texture and paint finishes that imitate stone, brick, or marble. Increasingly, digital fabrication tools such as 3D printing are expanding what’s possible in stage design.

With community productions in particular, it’s common for a set to be constructed using pre-assembled “flats” of standard shapes and sizes. Thus, scenic designers usually cater for their use as part of their construction planning.

During the get-in, the set is assembled on stage (the majority of theatre productions being rehearsed/prepared outside of the theatrical production venue beforehand). The designer supervises this process, ensuring the finished product matches the design intent. During technical rehearsals, adjustments occur as lighting, sound, and blocking are integrated. The scenic designer continues to collaborate, tweaking colours, materials, or configurations for optimum effect.

Creating Realism

One of the oldest functions of scenic design is to create realistic environments — spaces that convincingly reproduce the world outside the theatre. Realism invites audiences to believe that what they are watching is happening “for real,” grounding the story in a specific, recognisable place.

Realistic sets demand attention to detail and authenticity. A designer working on a Chekhov play might research Russian country homes of the late 19th century, considering architectural features, furniture, and even the patina of age on wallpaper. Every prop and piece of moulding must tell a story: a worn chair suggests family history; a cracked window hints at economic decline.

Lighting enhances this realism — soft daylight through gauzy curtains, warm lamplight for intimacy, or cold morning shadows to evoke tension. Texture becomes essential: wood grain, plaster walls, brick surfaces — all carefully painted and treated to appear natural under stage light.

However, scenic realism is not merely imitation. It’s a selective art — the designer must decide which details matter most to the storytelling. The audience doesn’t need to see every item in a kitchen; they need to feel the essence of that kitchen. Good scenic realism focuses attention without overwhelming it, giving actors a believable space to inhabit while keeping the visual storytelling clear.

Creating Fantasy & Abstraction

While realism offers familiarity, fantasy and abstraction invite imagination. In many productions — from Shakespeare to modern experimental theatre — scenic designers break away from literal representation to create symbolic or dreamlike worlds.

In a fantasy design, visual rules can be bent. Gravity, proportion, and time may not apply. Floors may curve upward, walls may float, and colours may pulsate. The scenic designer becomes a painter of emotion and metaphor; for example:

- In Alice in Wonderland, the world might distort in scale — oversized furniture or tilted doorways conveying the surreal quality of Alice’s journey.

- In Metamorphoses, a pool of water might serve as both a literal and a symbolic setting — at once a bathhouse, a sea, and a reflection of the human soul.

- In The Lion King, designer Julie Taymor famously merged masks, puppetry, and abstracted scenic shapes to create an otherworldly but emotionally truthful representation of nature.

In abstraction, a single object or colour can carry great symbolic weight. A bare tree on an empty stage might represent isolation (as in Waiting for Godot), whilst a translucent scrim might separate reality from memory (as in The Glass Menagerie). Such designs rely on the audience’s imagination to complete the world — a fundamental principle of theatre’s magic.

Scenic designers working in fantasy and abstraction often collaborate intensively with the lighting and projection designers. The interplay of light, shadow, and projection can transform static scenery into a living organism, allowing the environment to shift fluidly with the story’s rhythm.

Set Design as Storytelling

The set is not just background; it’s an active participant in the drama. A well-designed set can evolve alongside the story, reflecting changes in mood, character, or time. For instance:

- A house that appears pristine in Act I might decay over time, revealing the emotional deterioration of the family within.

- Movable panels might close in gradually, tightening the space as the tension builds.

- A revolving stage might literally turn the world upside down to represent moral inversion or chaos.

Scenic transitions themselves can be dramatic moments. The way in which a set changes — whether through blackouts, visible shifts, or automated rotations — can express as much emotion as a line of dialogue. Some productions even treat the act of transformation as part of the storytelling: walls glide, furniture folds, or projections morph in real time to mirror the characters’ psychological states.

Balancing Art and Function

A stage set must be as functional as it is beautiful. It must withstand repeated performances, quick scene changes, and the physical demands of actors. Doors must open reliably; furniture must support movement; sight-lines must remain clear for every audience member. Good design doesn’t draw attention to itself for its own sake; rather, it allows the story to shine.

This balance between art and practicality is part of the scenic designer’s mastery. Every element must serve multiple purposes: storytelling, safety, and efficiency. A trapdoor might conceal a surprise entrance; a painted floor might guide lighting focus; a unit set might transform fluidly to suggest multiple locations.

Sustainability and Innovation

Modern scenic design increasingly considers sustainability, with a scenic designer’s creativity extending to the environmental responsibility required to ensure the art form evolves sustainably.

The ephemeral nature of theatre — building elaborate sets for short runs — poses ecological challenges, and designers must be conscious when choosing materials and construction methods in order to reduce waste.

Pre-assembled “flats” of standard shapes and sizes are typically used as part of most scenic design, particularly in small/community productions.

Recycled wood, modular structures, and the use of reusable stock scenery are not uncommon. Digital projection offers an alternative to physical construction, creating expansive environments with minimal physical footprint.

More often than not, it can be more cost-effective to hire in pre-built staging and other scenic items, particularly for musical productions that have a community origin and/or short runs.

Leave a Reply