Theatre is one of the oldest and most enduring forms of artistic expression: it’s a collaboration across the many folks — the writers, actors, designers, and technicians — that make up any theatrical troupe.

As with any collaborative endeavour, each member of the team needs to feel like they’re empowered to perform their part in the production. However, without some overarching force that unites these diverse creatives into a cohesive whole, the chances of producing a successful outcome are slim at best.

The job of providing this overarching force falls to the Director. The role of the Director is arguably one of the most challenging, yet most rewarding, as they are essentially the artistic architect of the entire production — ensuring that every element, from lighting to line delivery, contributes to a unified vision.

The Director’s role is both visionary and practical: they interpret the script, shape the performance, guide the design process, and oversee the transformation of words on a page into living, breathing performance art.

My name’s Peter Fernandez, and in this article, I’ll be exploring the role of the Director, tracing the directorial process from the first encounter with the script to the final curtain call of the last performance.

Juel Brown, the author of the Story Teller’s Handbook channel on YouTube, shares some interesting perspectives on directing a show, and I’ll be sharing some of her videos along the way.

Directing in a Nutshell

The Director’s role in a theatrical production is multifaceted — part artist, part organiser, part psychologist, and part visionary. From the first encounter with a script to the final bow of the closing night, the Director shapes not just the performance but the entire creative journey.

In essence, the Director is the bridge between the page and the stage, idea and embodiment, chaos and coherence. Their artistry lies not only in what they create but in how they empower others to create with them. Theatre, at its most powerful, is a living dialogue — and the Director is its chief conductor, ensuring every voice, every gesture, and every moment sings in harmony from the first read-through to the last curtain call.

| Stage of Production | Core Tasks |

|---|---|

| Choose the Script | Experience the play intuitively; identify themes and emotional arcs. Define the unifying vision in a way that can be easily articulated. |

| Assemble the Team | Starting with the key personnel, bring together the group of folks who will help build your creation. |

| Cast the Show | Choose the actors, selecting those who align with the directorial concept and the ensemble dynamic. |

| Rehearse | Conduct table reads, develop characters, block scenes, shape the pace. Integrate light, sound, set, and costume to form a polished and cohesive performance. |

| Perform the Run | Empower the Stage Manager, test audience response; observe, adjust, and maintain quality. |

| Reflect | Put the show to bed and pack the stage away. Then take a moment to evaluate process and outcomes, documenting insights for future work. |

No production runs perfectly: sets malfunction, actors fall ill, and cues misfire. The Director’s calm adaptability can determine whether a show survives a crisis gracefully or collapses under pressure. Clarity and consistency are vital, especially under the pressures of production deadlines, and great Directors understand that theatre’s imperfections often produce its most memorable moments.

Beyond an individual production, the Director can also shape the identity of a theatre company or national aesthetic. Visionary Directors such as Peter Brook, Ariane Mnouchkine, Julie Taymor, and Robert Wilson have transformed global theatre by pushing the boundaries of interpretation, technology, and cross-cultural storytelling.

The work of a Director can be both immediate — guiding one ensemble through one particular show — and long-term, influencing generations of artists and audiences.

Choose the Script

Every production begins with a script. The script is the document that structures and develops the story of a play, typically incorporating the essential artistic and technical details that also need to be performed.

Whether you get to choose the script, or it chooses you, the Director’s first reading should be pure and emotional, allowing instinctive responses to emerge. Without making immediate analytical notes, the Director should simply experience the story as an audience member would — feeling its rhythm, tone, and dramatic impact.

For the majority of Directors — particularly those directing for the first time — a pre-written script is typically the preferred choice (as opposed to opting for one written from scratch).

After the initial immersion, a Director would typically begin a more forensic reading. This includes identifying the central themes, plot structure, dramatic arcs, and the motivations of each character. Such a process would usually involve breaking down scenes into what is often referred to as “units” and “beats”, examining shifts in objectives and conflicts, as well as noting the rhythm of tension and release.

From this arises what is known to as the Directorial Concept — the unifying idea that will largely inform every artistic choice throughout the production process. For example, a production of Macbeth might be conceived as a political thriller set in a dystopian state, or perhaps as a supernatural meditation on guilt and ambition.

Whilst a Directorial Concept is synonymous with both stage and screen direction, in the world of TV and Film, it typically goes hand-in-hand with what is known as the Treatment.

The directorial concept is not a superficial aesthetic choice; rather, it’s an interpretive framework that clarifies the play’s meaning for both the cast and the audience. It’s crucial that a Director can articulate the concept clearly so that all collaborators — actors, designers, and technicians — share the same creative vision.

Budget Considerations

The script will have budgetary implications that a Director will also need to consider. Whilst working with a community or professional production company will typically provide you with support in this area (it being the job of the Producer or Production Company Manager to handle the purse strings), if you’re going it alone, then the cost of a production is down to you.

Many theatre directors — especially those directing for the first time — will likely seek out a local production/theatre company to work with. This provides a great way of reducing cost, as well as finding support, particularly for community endeavours

The complexity of a production will also have an impact on how much it will cost to stage the show. For example, a script that demands complex staging, lighting, costumes and/or musical accompaniment may require a larger venue, specialist equipment hire, and/or PRS licensing — all of which will typically increase cost. You may also need to pay members of your team, particularly if specialist skills or training are required.

A commercially available pre-written script will, in all likelihood, have an associated licensing cost as well, which will often be calculated taking into consideration factors like the number of performances and the expected audience sizes.

Consider too that a large production will typically mean more copies of the script are required (as in a copy of the script for each cast member, as well as for each member of the production team). If you have to purchase pre-printed scripts as part of any commercial licensing, then this will also have an impact on the overall cost.

Venue Implications

A larger production will typically require a larger venue: a musical production, for example, is difficult to cast on a small stage as space is needed to accommodate (lavish) scenery, the chorus, dance routines, etc. From a budget perspective, the larger the venue, the larger the cost will likely be.

Working with a local production company (particularly for community endeavours) can again be beneficial, as many have access to what is often referred to as their “home” venue, for which they have priority use and at a discounted rate.

A production may also require specific venue capability. Again, a musical production will likely require an orchestra, so a venue will require some sort of orchestra pit and/or a corresponding sound stage to match. The ability to lower scenery onto the stage may also be required, so a fly-floor/fly tower setup will be needed. Or a show may require particular set change(s), necessitating a scene dock of an appropriate size.

Venue capacity is also a consideration. If you’re directing a show that costs a lot to stage, then you’re going to want to accommodate as large an audience as possible, especially if you have a limited run of production dates. Again, from a budget perspective, the larger the venue, the greater the cost is likely to be.

Availability of a venue must also be taken into consideration. If a script is geared towards a particular genre that lends itself to a particular time of year — a Pantomime production, for example, is typically staged around late December, early January — then you will need to confirm venue availability.

Consider too that particular times of year might impact audience attendance — if a venue is only available during the winter months, when the weather in your region could be particularly challenging, then audience attendance might be lower than expected/desired.

Conversely, an off-season venue might be an attractive proposition as the cost of venue hire may be significantly less.

Rehearsal Space

In many cases, you won’t be able to rehearse your show in the same place you stage it: either the venue doesn’t have a separate rehearsal space, a separate rehearsal space that’s reasonably priced, or there just isn’t the availability for the facilities on offer. So a separate rehearsal space will often be required.

I talk more about the rehearsal process below, but for now, just consider that your chosen production will have an impact on your rehearsal room requirements, which in turn will almost certainly have an impact on the budget for your show.

Timeline

The script you choose will affect the time it takes to take your show from concept to opening night. Some bespoke script that has never been performed before, for instance, will typically require a longer rehearsal period than a commercial script that has already been staged many times.

Many contemporary productions are devised collaboratively, meaning the script emerges from workshops and improvisations rather than a pre-written text. In such cases, the Director acts as curator and editor, shaping collective creativity into a structured form. Again, devised pieces often require more time than would otherwise be prescribed

Research and Preparation

Before the audition process (discussed in more detail later), and certainly before entering the rehearsal room, the Director may need to conduct extensive historical and cultural research, depending on the script chosen. Understanding the period in which the play was written, the playwright’s biography, and the social context can enrich interpretation. For example, staging Ibsen’s A Doll’s House without grasping the late 19th-century attitudes toward gender and marriage risks superficiality.

The Director must also consider style and genre — whether the play demands realism, expressionism, absurdism, or another mode; each style has its own conventions of movement, speech, and design. For instance, a Brechtian production emphasises alienation and social critique, requiring visible scene changes and direct audience address, whilst a Stanislavskian approach strives for psychological realism and emotional truth.

Assemble the Team

You have the Script and you’ve done the necessary due diligence, and largely this has been a solo affair — or possibly a collaboration between you as the Director and your Producer. At this stage, you’ll now start to assemble your production team, or at least the key personnel.

Meeting with the production team — i.e. the team of set, costume, lighting, and sound designers — a Director will begin by translating their concept into tangible form, and sketches, research images, and storyboards are often exchanged at this stage.

The production team will likely meet multiple times throughout the course of the production process, and more than one production team meeting is often the norm before entering the rehearsal room.

This meeting will essentially be your initial discussion, where ideas are exchanged and where concerns can be raised — or at least enough exploration is done to highlight any items for subsequent consideration.

For instance, at or after your first production meeting, your Set/Scenic Designer might provide what is known as a Model Box, translating some two-dimensional stage plan into something easier to imagine in a three-dimensional space (before set construction commences).

Remember, the Director’s job is to guide rather than dictate — allowing designers creative freedom. However, ensuring all visual and auditory elements align with your directorial concept is important; the earlier you can establish authoritative rapport in collaboration, the less disjointedness you will encounter later in the production process.

Key Personnel

There’s no hard and fast rule, per se, when it comes to building your team, and it largely depends on the production you’re looking to stage. As a rule of thumb, I’d recommend selecting your Stage Manager at the outset — your key companion in the rehearsal room (more on that below) — as well as your Set/Scenic Designer, and then look to add your Lighting Designer and Sound Designer and all the other members in your crew in quick succession.

Ideally, before your first production meeting, my recommendation would be to have the the following key personnel in place, and I’ll be talking more about each of these roles in future articles:

- Stage Manager

- Set/Scenic Designer

- Lighting Designer

- Sound Designer

- Head of Set Building (otherwise referred to as the Master Carpenter)

- Optional, but well worth doing if perhaps your set might be difficult to construct.

Cast the Show

Casting is one of the Director’s most critical responsibilities. The right actor can bring a role to life; the wrong one can compromise an entire production. Auditions test not only talent but also chemistry, energy, and interpretive instincts.

The Director should enter auditions with clear character breakdowns and a flexible mindset. Sometimes an actor reveals a new facet of a role the Director hadn’t imagined, so it’s important to keep an open mind, allowing one to adapt to such discoveries.

While strong individual performances matter, the overall ensemble dynamic often defines a production’s success. The Director must ensure that casting choices create balance between the likes of ages, energies, and acting styles so the cast operates as a unified organism.

In modern theatre, the role of the Director has evolved from autocratic auteur to cultural facilitator, and modern Directors carry the responsibility to foster representation and accessibility — reinterpreting classical texts through inclusive casting and contextual framing.

Play Readings

In the world of community theatre — the world that I mostly get involved with — it’s often the case that one or more play readings of an upcoming production are organised prior to auditions taking place. Community theatre typically prioritises folks getting together for a good time, more so than a profit-making exercise, so the opportunity to arrange play readings is a fun thing to do.

It’s also good, because a play reading doesn’t necessarily have to be for an upcoming show; reading evenings can be a great vehicle for giving would-be Directors, particularly those directing for the first time, an opportunity to explore different genres and different works that might spark a passion!

Casting Calls

Before auditions, the Director (or the production group/company with which they are working) will typically advertise the fact that an upcoming production is looking for Actors/Actresses to fill the required roles. This is typically referred to as the casting call, and you will likely have more than one before you finally cast the show.

If you have a website, advertising casting calls on it is a great way to get the message out. Alternatively, or in addition, social media platforms like Facebook often have groups specifically for advertising this sort of thing.

Announcing your casting call(s) in good time will ensure that you have the best chance of finding the right individuals for your production and, as a minimum, you should include the following information in your advertising:

- Name of the show

- Including a brief synopsis is also a good idea

- Who is producing the show

- As in the name of the production company if any is involved

- The list of cast required

- Include a brief characterisation and the suggested age range for each character, and also whether it’s a lead or supporting role.

- Date, time and location of auditions

- Or at the very least some contact details

Rehearsal Planning

Together with the Stage Manager, the Director will come up with a rehearsal schedule that sequences work efficiently — starting with table reads, moving through scene work, blocking, run-throughs, etc.

How many rehearsals you should schedule and what your rehearsal schedule should look like is largely down to the production being staged; the script will typically dictate your rehearsal schedule, as Juel points out in her video (below). I’ll be writing an article that goes into more detail on the rehearsal process at some point in the future, so stay tuned for that 😎

Whilst the rehearsal schedule must account for actor availability, design deadlines, and production milestones (such as technical rehearsals and any previews), having some sort of rehearsal schedule available ahead of auditions — at the very least, some idea of the days and times that you’ll be rehearsing — will give folks who want to be involved the opportunity to see if it fits with their plans.

In the video below, Juel Brown does a great job of covering much of what’s been discussed so far — as well as setting the stage for what’s to come 😎 So before we move on, feel free to take a moment and watch Juel recap on what we’ve covered so far:

Rehearse

As the ultimate editor of time, a Director will guide a production through the use of careful pace, control of tension, comic timing, and dramatic buildup. Rehearsals are the laboratories for finding that rhythm — too slow and energy fades; too fast and meaning is lost.

During the rehearsal process, the Director gives targeted feedback, focusing on the adjustments that need to be made; successful direction brings together words, movement, light, and emotion into a unified experience that transcends the sum of its parts, interpreting the playwright’s intent and harnessing the actors’ craft to guide the audience’s imagination — all while managing the complex machinery of live performance.

During rehearsal, a Director’s leadership comes to the fore, and must balance authority with empathy and compassion. Too much control stifles creativity; too little invites chaos. The ideal Director fosters an environment of trust, where actors feel safe to take risks. They must also mediate conflicts, manage stress, and maintain morale — qualities often as important as artistic vision.

Directors wield significant influence over actors’ emotional exposure, designers’ workload, and the overall cultural message of a production. Directorial ethics should respect boundaries, ensure safety, and cultivate inclusivity.

The Director should also be conscious of representation and power dynamics, particularly when staging works that engage with gender, race, or trauma. So the rehearsal room should be a space of collaboration, not one of coercion.

Director’s Notebook

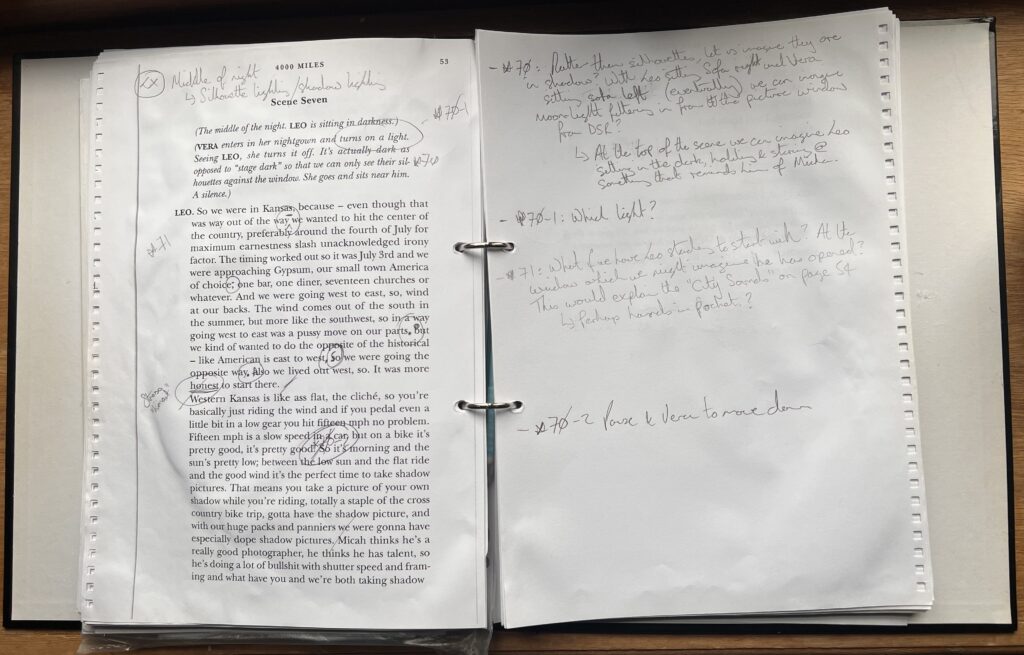

Before rehearsals begin, most Directors create what is typically referred to as the director’s notebook — a guide containing scene analyses, blocking notes, thematic commentary, and design references. It’s a living, breathing document that’s compiled progressively, and that serves as both a creative roadmap and a communication tool for stage management and designers. By way of example, here’s an excerpt from my director’s notes/notebook for the production of 4000 Miles I staged a little while back :

I like to create a notebook by enlarging each page of the script to a single sheet of A4, all of which are then bound using a ring-binder. I can then make notes against each page of the script, utilising the blank backside of the page that follows.

The Rehearsal Room

The term “rehearsal room” refers to the space in which you are going to be rehearsing. It should be fit for purpose, large enough to accommodate the work — dance rehearsals for a musical, for example, will typically require a space larger than the one used for classic acting — and also comfortable: a rehearsal will typically go on for a few hours or more, so somewhere to get water or make a tea/coffee is always welcome.

Table Read

The first rehearsal, often called the “table read”, is an essential foundation. The cast gathers to read the script aloud, discuss characters, and clarify unfamiliar terms or references. The Director uses this session to share the artistic vision, themes, and emotional tone of the production.

Blocking

Blocking — the planned movement of actors on stage — is where the Director’s visual imagination becomes concrete. Good blocking balances composition, focus, and motivation, where movement should arise naturally from a character’s objective rather than being imposed arbitrarily. I’ll be covering more on the blocking process in a future article.

Blocking is often refined over many rehearsals as the Director observes what feels authentic and what disrupts the emotional flow. Early rehearsals are exploratory: this stage is about generating possibilities, not fixing results. The Director encourages experimentation and improvisation so actors can discover relationships and motivations organically.

Characterisation

Directors must nurture emotional authenticity. Using techniques drawn from personal experience, or from recognised sources such as Stanislavski, Meisner, or other acting methodologies, they guide actors to find real motivation behind lines and gestures. A skilled Director helps actors connect deeply to the text without micromanaging their instincts.

Integrating Design Elements

As rehearsals progress, technical elements begin to integrate: lighting cues, sound effects, costume fittings, and set transitions. The Director coordinates these components so they support the story rather than distract from it.

Run throughs

Up to this point, rehearsals will have typically been a stop-start affair, where the Director guides the production a piece at a time — little by little moulding the shape of each part of the script. During a run-through, the Director should resist the temptation to stop and start, preferring to let the actors run through an entire show (or Act) before providing feedback based on the notes they’ve made.

During the run-through phase, I like to start by doing an Act at a time — giving my Director’s notes over a tea/coffee break, say — before switching to giving notes after an entire show run-through.

Technical Rehearsal

Technical rehearsals are often gruelling; yes, I’ve used the plural here because there may be more than one required (“Tech Week” is often the term used for this stage of the production process). During this process, the Director must balance patience and precision, ensuring that every cue enhances the storytelling, all while maintaining morale in the room.

The Director, stage manager, and technical team synchronise lighting, sound, projections, and scene changes with the actors’ performances. Timing becomes crucial, and a lighting cue that lands half a second late can undermine an emotional beat.

Technology and Multimedia

Today’s Directors must navigate digital projection, live streaming, and virtual performance spaces, and more, as part of production tech rehearsals. Integrating technology without losing the human connection is a new balancing act.

By way of example, here’s a clip of a bespoke lighting rig (with additional projection) that I built for a production of Constellations — which, incidentally, I also directed. Whilst it had a lot of “teething” issues during the technical rehearsal, a pragmatic approach enabled the team to carry on whilst the gremlins were addressed 😎:

Dress Rehearsal

Dress rehearsals simulate actual performances, complete with costumes, makeup, and full technical integration; again, there may need to be more than one dress rehearsal before opening night! During the rehearsal, the Director observes quietly, taking notes rather than interrupting, to gauge the production’s overall flow and emotional impact.

Perform the Run

Once a production opens (i.e. transitions from rehearsal to performance), the role of the Director begins to shift. Their active intervention diminishes, and the Stage Manager takes over the job of maintaining consistency and control. However, the Director often attends early performances to monitor audience reactions and make minor refinements.

Even the best productions can drift over time as actors settle into routines. So, depending on the length of the run, a vigilant Director will check in periodically, reminding the company of key intentions and renewing focus. This ensures the energy and precision of the show remain consistent throughout.

Preview

Some shows have one (or perhaps more) Preview night(s) that occur before the “official” opening night. This is where a select audience — typically made up of peers, colleagues and often reviewers/critics — is invited to attend an early performance of the show.

During the preview phase, a Director will often adjust pacing or blocking based on audience feedback. Theatre is a live art form, and having a select audience as the final, unpredictable collaborator can help a Director shape the final outcome of a piece based on their response — i.e. laughter, silence, gasps, etc.

Not every production will have or even require a preview, but if it does, then it’s a great opportunity to make any last-minute tweaks.

Reflect

The final performance ends, and the curtain comes down for the last time; however, the Director’s job is not quite done. The “after-show party”, as it’s most commonly known, gives everyone the chance to unwind and celebrate what’s been achieved, and in community theatre in particular, gives a Director the chance to say a few final words.

Directors should also take the time to analyse what succeeded and what didn’t — artistically, logistically, and interpersonally. Many directors keep journals, or they debrief with the team to document lessons learned for future projects. Theatre thrives on continuous evolution, and each production contributes to a Director’s growing understanding of the art form.

Wrapping up, here’s Juel’s conclusion on being a Director, in the second half of the 2-part video from her Story Teller’s Handbook channel on YouTube:

Leave a Reply