Theatre is a space for stories that are both intimate and universal. Unlike film or fiction, the stage offers no escape into special effects or quick edits; it relies entirely on words, bodies, and space. The art of writing a theatrical play lies in balancing imagination with precision. It demands a clear vision, distinct voices, meaningful conflict, and a respect for the constraints — and possibilities — of live performance.

Writing for the stage is, therefore, both an art and a discipline. It requires not only imagination but also an understanding of the practical and emotional mechanics of theatre. A play must live through dialogue and action — through human presence in real time — and to write an effective stage play, a playwright must think like a storyteller, a director, an actor, and even a stage manager, all at once.

My name’s Peter Fernandez, and in this article, I’ll be exploring the art and craft of playwriting: how to shape compelling scripts, avoid common writing traps, and ensure that your final play is ready to live and breathe before a live theatre audience:

| Introduce Conflict | Every scene needs tension; without it, the play stalls. |

| Avoid Information Dumping | Trust the audience’s intelligence; show, don’t tell. |

| Avoid Too Many Locations | Simplify: embrace theatrical imagination instead of cinematic sprawl. |

| Avoid Filler Dialogue | Cut what doesn’t reveal or advance. Use silence intentionally. |

| Avoid Weak Character Voices | Differentiate through rhythm, vocabulary, and worldview. |

| Avoid Unfocused Structure | Know your central theme and stick to it. |

| Edit Relentlessly | Rewrite multiple times; test through multiple readings. |

Mindset of a Playwright

Playwriting is not about chasing perfection; it’s about curiosity and empathy. A play explores fear, desire, contradiction, and hope — all under the magnifying glass of live performance. It asks: What does it mean to be human?

A play doesn’t exist in isolation — it’s a conversation with an audience. Audiences come to the theatre to feel, to think, and to witness transformation. Balance emotional truth with intellectual substance.

Unlike television or film, theatre depends on immediacy. A whispered confession or a sudden silence can resonate more deeply than a thousand cinematic cuts. Write moments that live in the shared breath of the room — the best plays leave audiences reflecting long after the curtain falls. Ask yourself: What do I want my audience to carry home?

To write a play, then, is to enter a dialogue with time, space, and people. It’s an act of generosity and risk. That’s the essence of theatre — and the playwright’s greatest gift; as the American playwright Paula Vogel once said:

“Plays are not written to be read — they’re written to be performed, to make people gather in a room and imagine together.”

Not uncommon, particularly amongst community theatre groups, play readings are great fun and a valuable exercise. However, one must remember that a script that doesn’t “read” well is not necessarily indicative of a bad play!

Writing for the stage means crafting an experience that only theatre can provide: a world built from words, made real by presence. Write boldly. Edit ruthlessly. Listen deeply.

And above all — remember that a play is not complete until it meets its audience.

The Collaborative Nature of Playwriting

Playwriting requires humility: the willingness to let your work evolve beyond you. Unlike novels, a play is never complete on the page; it only becomes itself when interpreted by others.

Workshop and Development

Hearing actors perform your text is transformative. You’ll discover where dialogue feels forced, where scenes lag, and where emotion rings true. Many theatre companies/groups offer workshopping opportunities — informal readings where playwrights can test their work. Treat feedback not as judgment, but as collaboration.

Remember, a script that has never been performed before will typically require a longer rehearsal period than one that has been staged many times.

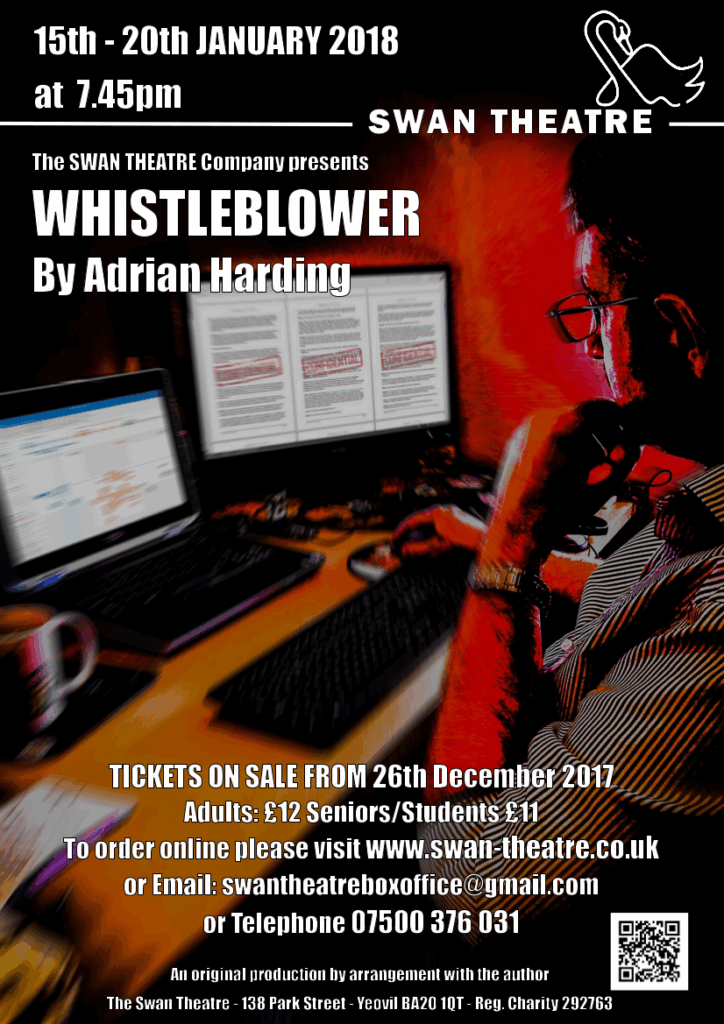

I recall a production of Whistleblower (a debut play by Adrian Harding) in which I played the male lead. Although we’d workshopped the development of the production over a number of iterations, as an actor, the most challenging thing for me was to try and learn a part — for which dialogue and characterisation were changing as we rehearsed — in the same amount of time as we’d have typically given to a script of a more mature nature. We made it work, but it taught me a thing or two that I’ve taken on board since.

Working with Directors

A director may interpret your script differently from how you envisioned. Stay open. Theatre thrives on collaboration. Your words are the blueprint — but others will help build the structure.

A Balance Between Structure & Freedom

While understanding structure is crucial, rigidity can suffocate creativity. Some playwrights — like Tennessee Williams or Caryl Churchill — begin with images or emotions rather than outlines. Others, like Arthur Miller, meticulously plan each beat before writing dialogue. Find the balance that suits your process. The key is to keep both the heart and the architecture of your play alive.

Nature of a Play

Before discussing how to write one, it’s worth defining what a play actually is. A play is not just a story told through dialogue, but is a live event — every line, silence, and movement exists in real time and space as a shared moment between actors and the audience. A great play feels both inevitable and alive: inevitable because every moment belongs exactly where it is, and alive because it surprises, breathes, and moves.

Unlike novels, plays cannot rely on internal monologue, long exposition, or shifting cinematic locations. Everything must be communicated through dialogue, conflict, and action that can be performed in front of an audience. Writing for the stage means thinking in terms of what can be done, not just what can be said:

“A play is not a message — it’s an experience. You don’t write it to tell people something; you write it so that something happens to them.”

Tom Stoppard

The Structure of Drama

The structure of a play is the roadmap that shapes the story’s rhythm and flow. Unlike film, which can use editing, or novels — which can shift perspectives freely — a play must progress in real time and space before a live audience.

A strong, dramatic structure ensures that tension builds steadily, revelations occur with purpose, and the audience remains emotionally engaged from beginning to end. At its simplest, a traditional play follows three key movements, typically divided into the Acts and Scenes that form the fundamental building blocks of stage storytelling:

- Setup – Establishes characters, situation, and conflict.

- Confrontation – Deepens conflict and raises stakes.

- Resolution – Brings the story to a climax and conclusion.

Acts

An act is a major division of a play, typically representing a distinct phase in the story’s progression. Each act contains a series of scenes that develop the plot and characters within the dramatic arc (discussed in more detail below).

Originating in ancient Greek and Roman theatre and refined by Renaissance playwrights like Shakespeare, the five-act play structure became a standard model for centuries. It offers a clear, symmetrical rhythm that allows for gradual buildup and satisfying release, and is typically seen in plays like Hamlet or Romeo and Juliet.

In modern theatre, the two-act play is the most common format. The first act typically sets up the world and escalates conflict, while the second act deepens and resolves it:

- Act I: Introduces the world, key characters, and primary conflict, ending on a turning point or revelation.

- Act II: Explores the aftermath, drives toward climax, and concludes with resolution.

Three-act plays are not uncommon, where the first act introduces characters and the conflict, the second develops the conflict, and the third provides a resolution.

The interval (or intermission) between acts provides audiences with a pause — both to rest physically and to reflect mentally on what’s been seen.

Shorter plays, often 20–60 minutes long, compress the entire dramatic journey into a single, unbroken act. This form demands tight focus, minimal exposition, and efficient storytelling. These one-act plays are especially common in festivals, community theatre, and educational settings, and can be deeply powerful — offering a concentrated burst of dramatic energy.

Scenes

If acts are the “architecture” of the play, then scenes are the rooms within it. Each scene represents a discrete unit of action — a moment where something changes.

A scene should always have a clear dramatic purpose, and at the end, the situation should be different from when it began. This sense of movement keeps the audience invested and propels the story forward; a scene might:

- Advance the plot.

- Reveal character or relationship.

- Increase or resolve tension.

- Provide crucial information through action rather than exposition.

Transitions between scenes are more than technical necessities — they are part of the rhythm of the play. In realistic plays, scenes may end with a clear blackout and a change of set, whilst in more fluid or symbolic works, scenes may blend seamlessly through lighting, sound, or movement. Regardless of style, each transition signals a shift in time, place, or emotional state, with smooth, purposeful shifts helping to maintain momentum.

Long, dialogue-heavy scenes can build psychological depth, while short, sharp scenes increase energy and urgency. A well-balanced play alternates between these rhythms, giving audiences moments of tension and release. This is referred to as pacing, and is the heartbeat of a play; the goal of the playwright being to vary pace without losing coherence (too many quick scenes can feel fragmented, while too few can feel static).

Lines

Lines are what the characters in the play say — a.k.a. the dialogue — and often carry some indication of the way in which the dialogue should be delivered and/or some action that should be associated with that delivery. For example:

SARAH: (glancing at the suitcase) You packed light this time.

MAYA: I learned my lesson. I don’t plan on staying long.

Exposition-heavy introductions — as in, “As you know, I’m your sister who left town ten years ago” — should be avoided, preferring relationships and history to be revealed organically through subtext and behaviour. In the lines above, we sense history, distance, and unspoken tension — all without a single expository statement.

Characters

When it comes to the actual characters, not everyone needs to appear in the first scene; staggered entrances allow for dynamic layering and anticipation. Introducing a key figure later can create suspense or shift the play’s power dynamics, and when done thoughtfully, each new arrival adds fresh energy and complexity to the story.

The Engine of Drama

Within its acts and scenes, a play must contain some form of conflict between the characters — either something new or a continuation/re-visitation of something that already exists. Without conflict, there is no drama, only conversation.

Conflict, however, doesn’t always mean shouting or violence; it means opposition. Characters in a play typically want different things, or perhaps the same thing in different ways. An effective play typically combines one or more of the following:

- Internal conflict: Within a character’s own heart or mind.

- External conflict: Between characters, or between a character and society.

- Environmental conflict: Between a character and circumstance — time, place, or nature.

Conflict Escalation

Each scene within the play should increase tension or shift the balance of power: conflict that remains static loses energy. As the playwright, ask yourself after each scene: Has something changed? If not, rewrite. An audience must always sense forward motion, emotionally or intellectually.

Even plays where the audience is taken back in time, as some “retrospective”, still keep the story moving forward, regardless of the twists and turns.

Conflict Resolution

A satisfying play provides closure, but not necessarily comfort — what matters is that the ending feels earned. The resolution should answer the central dramatic question and reveal transformation. In King Lear, for example, the resolution is devastating but inevitable; in The Importance of Being Earnest, it’s joyous and absurd.

Creating Clear Focus and Direction

Many new plays falter because they lack a clear and central focus that guides every scene. Ask yourself: What is this play really about? Not the plot, per se, but the core emotional or philosophical question. For example:

- Death of a Salesman is about the conflict between illusion and reality.

- A Doll’s House is about freedom and identity within societal constraints.

- Hamilton is about ambition and legacy.

Once you know your central question or theme, everything in the play — every act, every scene, every line — should serve it.

Shaping a Dramatic Arc

Theatre is built on momentum. A play must start with a disturbance, build toward a crisis, and resolve with change. Even in non-linear or avant-garde theatre, there must be some progression — a journey that pulls the audience forward, and a simple but effective structure will typically follows an established path:

- Exposition – Introduce characters and situation.

- Inciting Incident – Something disrupts normality.

- Rising Action – Conflict deepens, stakes rise.

- Climax – The turning point or confrontation.

- Resolution – The aftermath; how things have changed.

Avoiding Structural Confusion

Don’t overload your play with subplots or tangents. Audiences have limited time to follow the story; every scene should either advance the plot or deepen a character. If a scene could be cut without affecting the story, it probably should be.

Building Characters

A great play depends on great characters. In theatre, the audience learns who a character is not through narration, but through what they say and do. The best characters have clear objectives that drive their choices and fuel conflict. Before you begin writing, spend time understanding your characters’ backgrounds, desires, and contradictions. Ask yourself:

- What do they want?

- What stands in their way?

- What do they fear losing?

- How do they change by the end?

Distinct Voices

Actors rely on voice distinction to build their performances. A well-differentiated voice helps them — and the audience — connect. Each character’s education, background, temperament, and emotional state all influence how they speak. Read your dialogue aloud; if all characters sound interchangeable, adjust rhythm, vocabulary, and tone until they sound unique.

Subtext Over Statement

Avoid writing dialogue that states feelings directly. In life, people rarely say what they truly mean; they hint, deflect, or mask. The tension between what’s said and what’s felt creates dramatic richness. For instance, instead of a character saying, “I’m angry you left me,” they might say, “You always were good at walking away.” This subtlety invites the audience to lean in and participate emotionally.

Avoid Information Dumping

One of the most common mistakes in playwriting is information dumping — when characters explain the plot or backstory in unnatural ways.

“As you know, Margaret, ever since Mother died and Father remarried your best friend’s cousin…”

Feels false because real people never talk like that, and theatre audiences are quick to recognise exposition disguised as dialogue:

- Show, Don’t Tell: Reveal information through action, conflict, and subtext rather than explanation.

- Instead of telling us a marriage is strained, show it in how they avoid touching or talk past each other.

- Let the Audience Catch Up: Audiences enjoy piecing things together. Trust them to infer details gradually.

- Use Conflict as a Vehicle for Exposition: Information lands naturally when revealed through disagreement or emotional stakes.

For example, in the following, we learn the key information — that someone died and there’s estrangement — without a single expository paragraph:

SARAH: You never came to the funeral.

JAMES: I didn’t think you’d want me there.

Avoid Filler

Filler dialogue — i.e. conversation without purpose — is the silent killer of stage plays. It may sound realistic, but in theatre, every line must either reveal character or advance the story. After writing a scene, ask yourself the following, and if it doesn’t pass the test, trim or rewrite it:

- What changes during this exchange?

- What does each character want?

- If I cut this scene, would the play still make sense?

Use Silence Purposefully

Not every moment needs dialogue. Silence, when intentional, can be far more powerful. Pauses allow emotion to breathe and tension to build. For example, the playwright Harold Pinter famously used pauses as weapons — moments where what isn’t said speaks volumes.

Managing Location

The stage is a living, physical space, not a film set. Too many locations can create logistical nightmares and break the audience’s immersion. A script overloaded with complex locations, special effects, or large ensembles can be prohibitive for producers and directors. Practical awareness doesn’t mean limiting imagination — it means channelling it effectively.

Remember, constraints breed creativity: a simple bench and a window can suggest an entire world if the writing is strong enough.

Simplify Settings

Most successful plays use a limited number of locations — sometimes just one. A consistent setting allows focus on character and story rather than constant scene changes. If you need multiple settings, think creatively: can one space serve multiple purposes through lighting, minimal set changes, or symbolic design?

Sculpting the Final Draft

Great writing is rewriting: don’t be afraid of rewriting extensively. The first draft of a play is rarely more than a sketch of potential. Some of the greatest plays in history underwent dozens of drafts. Each pass should deepen characters, sharpen conflict, and strengthen pacing.

After finishing a draft, take a break. Distance allows objectivity, and when you return, you’ll see pacing issues and redundancies more clearly. Invite constructive critique from directors, actors, or dramaturgs. Others may notice structural flaws or inconsistencies you’ve missed.

Because plays are meant to be heard, not just read, reading aloud is essential. Better yet, gather actors or friends for a table read. You’ll quickly hear what drags, what sounds unnatural, and what sings.

If you love a line but it doesn’t serve the story, cut it. As the saying goes, “Kill your darlings.” Whilst editing is essentially about reduction, it’s about refining the story — the goal being to achieve clarity and rhythm, not necessarily reducing the length.

Juel Brown — Artist, Director, Author and creator of the Story Teller’s Handbook channel on YouTube — has this to say about writing a play:

Leave a Reply